“It would be difficult to learn when the poultry industry began in this district; but the co-operative association began in 1921. Mr. H.F. Williams of Poplar was one of the prime movers and was elected president of the association. Ed. E. Taggard was elected vice-president; C.A. Cohenour, secretary; and P.M. Morrison and J.C. Snider, directors. The association bought the feed store of Nance and Yates, which had been established earlier by W. Yates. J.W. Nance was made the first manager. About 40 producers of Poplar and also of Porterville were members. Among large producers of the association were H.S. Williams, Marion Crabtree (who had from 5000 to 6000 hens), George Brand, and Frank Norman. Les Hayes, a large producer, was not in. These were egg producers. Among the chicken producers or hatcheries were Dr. Hearn, Frank Penn, and the

Benedict Hatchery, of the immediate vicinity of Porterville, Harry Taggard of Poplar, Marlow west of Strathmore, Vogel of Tulare, and C.V. Kiger of Terra Bella. C.V. Kiger settled 41/2 miles southeast of Terra Bella in 1920 to raise fruit but finding he couldn’t make a living at that said he started the chicken business “on a shoe-string” dimension; and in 1934 at one hatching had 15,000 chicks.

In 1925, because the association had extended so far beyond Porterville, its name was changed from Porterville Poultry Producers Association to San Joaquin Valley Poultry Producers Association. (A branch was opened in Fresno in 1933.) The territory now extends to Chowchilla and Madera on the north and Wasco and Shafter on the west. W.B. Roby succeeded Mr. Nance as manager in 1925. In February 1938, there are 938 members in the association (probably including about 65% of the local producers). 63 persons are employed. 23 trucks and cars are used to transport feeds to producers, gather eggs, and send these to the market in Los Angeles. Hardly any fowls are handled: the eggs are either Leghorn or colored. E.A. Mayer of Wasco is the largest producer; most producers have from 1000 to 2000 hens.” – (Mitchell p.24-25)

This building was located somewhere at Mill and D streets across from the Post Office somewhere? Before the post office?

1900 – TYPES OF POULTRY

1. Wyandottes. 2. Leghorns. 3. Orpingtons. 4. Hoodans 5. Game. 6. Plymouth Rocks. 7. Cochins. 8. Minoreas. 9. Brahmas. 10. Dorkings. 11. Langshans. 12. Hamburghs.

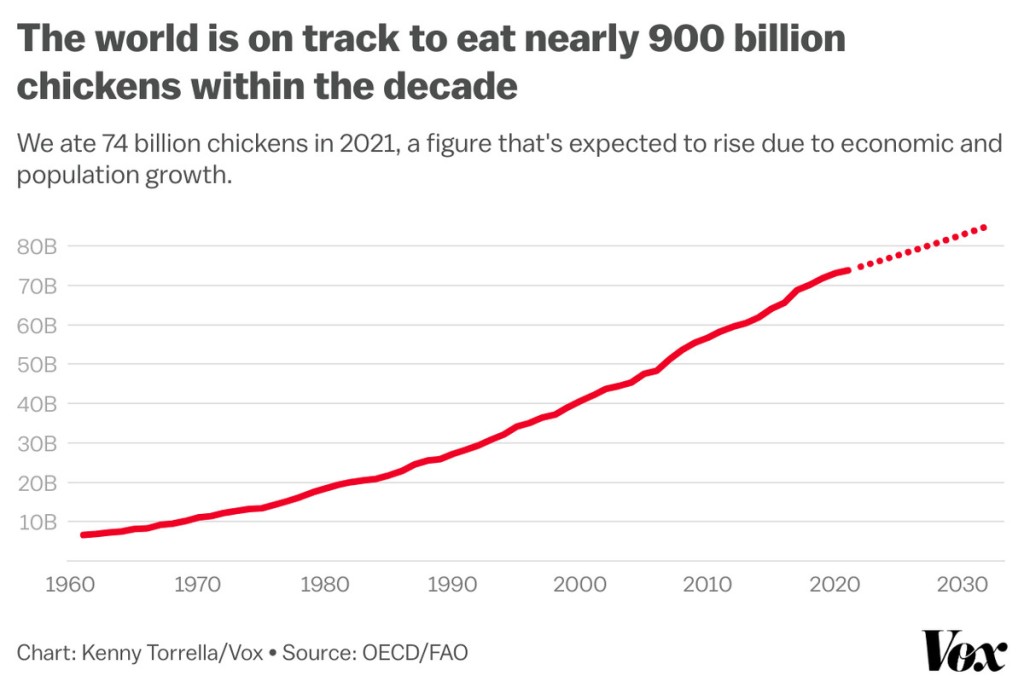

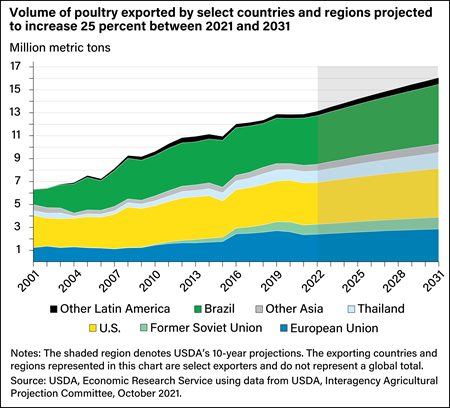

This is the story about Frank Gehring organized 200 poultry farmers into the Coop. But first, let’s understand Chicken’s history and future briefly.

“The modern chicken is a descendant of red junglefowl hybrids along with the grey junglefowl first raised thousands of years ago in the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent.

Chicken as a meat has been depicted in Babylonian carvings from around 600 BC. Chicken was one of the most common meats available in the Middle Ages. For thousands of years, a number of different kinds of chicken have been eaten across most of the Eastern hemisphere, including capons, pullets, and hens. (wiki)

In the United States in the 1800s, chicken was more expensive than other meats and it was “sought by the rich because [it is] so costly as to be an uncommon dish.” (source)

“In the early 1900s, American chickens were not considered necessary “livestock” animals on farms. Chicken meat was a delicacy, only served on special occasions and eggs were a luxury. Small flocks of chickens were only raised on rural family farms. Families with larger flocks (300 or more) sold eggs as their primary income.” (source)

“For most of American history, poultry and eggs were luxury foods. Chicken traditionally was far more expensive than beef or pork—after all, you needed grain to feed chickens, but cows could grow on grass and pigs could grow on garbage. For the first half of the twentieth century, the average person ate twenty pounds of chicken or less per year (approximately six chickens). By 1964, chicken had become more of a staple and people were consuming over a half pound per week—up to twenty-five to thirty pounds per year.1 Since then, we have continued to increase our chicken consumption almost every single year. As a result, chicken is now the number-one meat in the nation, with the average person consuming an estimated two pounds per person per week,2 or roughly one hundred pounds (thirty chickens) per year. In 2015, the average household ate chicken three to four times per week.

In 2016, America’s poultry industry produced over nine billion chickens. If the state of Georgia were its own country, it would rank as the fourth-highest country in the world for poultry production. As a result of this large-scale production, chicken has become the most affordable animal protein source at the grocery store, at times on sale for less than one dollar per pound. In contrast, beef and pork sell for around three to four dollars per pound. A prediction made in the 1940s—that chicken would become “meat for the price of bread”—has come to pass.3

A CHICKEN’S LIFE FOR ME

A lot had to change for chicken to become such a production powerhouse. Up until the mid-1900s, the majority of chickens were raised in small flocks (one to three hundred birds) on small family farms. When old laying hens retired, they became “stewing hens.” Excess young males were sold as “spring chickens.” With very little breast meat, neither of these resembled the chickens we cook today. The stewing hens were tough and required long, slow cooking to make them palatable. The spring chickens, although easier to prepare, produced a paltry two to two-and-a-half pounds of dressed bird for the dinner table. Both were extremely expensive.

” (source)

More Chicken Economics HERE

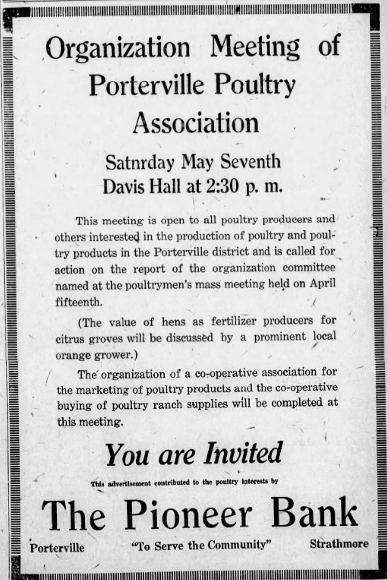

Dec 9th 1913 – The Association is formed.

10 Dec 1913

23 Nov 1918

Why Cooperatives?

Lindsay A. Crawford, assistant secretary of the Berkeley Bank of Cooperatives, gave the principal address at the annual meeting and dinner of the association. He said that his subject might be entitled: “Why Cooperatives?” The theory of cooperation, he pointed out, is found in the old, familiar adage that “united we stand, divided we fall.” This is probably the reason for cooperatives, he explained.

‘The Consuming public of America,’ said Crawford, ‘is a peculiar animal. The public is sold more and more on service. We could just as well get along without the fancy cellophane wrappings, but the public has come to demand fancy packages. Everything used to be grown and prepared on the farm; now we have prepared food in its wide variety. There is too great a spread between the farmer’s dollar and the consumer’s dollar. A great number of services are required before the product is marketed.

‘One outlet for better prices for our product,’ said Lindsay, ‘is to control more of our commodity through cooperatives. Cooperatives cannot control the law of supply and demand, but can see that commodities are marketed in a more orderly manner.’

Growth of Association

The association was organized in 1921 and was then known as the Porterville Poultry Association. The association was reorganized in 1925, with W. B. Roby as manager, and was then known as the Porterville Cooperative Poultry Association. In 1933 there was another reorganization, and the association became the San Joaquin Valley Poultry Producers Association, operating in five South San Joaquin valley counties, and with a branch office at Fresno. The gross business of the association has grown from a humble beginning to close to $2,000,000 annually. The membership has increased from 92 in 1925 to 1,048 in 1939. The assets of the association are now listed at $277,909.04.

New Board of Directors

Paul Barthel of Porterville, reporting for the election committee, and that W. G. Geres of Terra Bella and J. D. Sailors of Poplar, both long time members of the board of directors, had been re-elected to the board. J. C. Parker of Frenso was elected a new director. The holdover members of the board are: George W. Brant and L. C. Baker of Porterville, M. Michaelson of Madera, W. W. Arkley of Orange Cove.

Sailors was president the past year, F.M. Crabtree secretary of board.

S. W. Adams oldest employee of association.

H.S. Williamson, the first president.

(Feb. 20, 1940)

20 Apr 1921

04 May 1921

25 May 1921

“A peculiar phase of the situation is that almost every producer who has attended the meetings has signed up and is a hard worker and booster for the proposition. The poultrymen who have not been present at the meetings are skeptical and want the details of the formation of the association explained to them. It is practically impossible for the members who are working in the interest of the community and association for nothing, to do this as they haven’t the time to spare. If these men, who are poultry raisers and would derive direct benefits from the organization, would make it a point to be present at these gatherings all questions would be cared for as they are answered at the meetings.

Mr. Gehring also stated that another thing they had to fight against was the state of mind of the small producer who assumes that his small producer who assumed that this total production of hens and eggs isn’t large enough to warrant his membership. “This is a false impression,” stated Mr. Gehring to a Recorder scribe today. “The benefits derived by the smallest producer in this section would in six months pay back to him his membership fee.” The main item of expense for membership is then over, but the benefits will continue as long as the man produces eggs, hens and buys feed.

Local poultry men, who commenced the organizing, are disappointed because of the lack of interest shown by Porterville and vicinity. One of these men stated this afternoon that if the local association was not formed they would join the Tulare organization and handle their business through that city.

The outside money which comes into Tulare, through the Poultry Association, is about $75,000 per month. With a little effort the local poultry checks would equal, if not surpass, the Tulare checks. Of course a large percentage of this money would be spent with local merchants, thereby benefiting the community at large.

The Poultry Association is deserving of support of every business man in Porterville. (May 25, 1921) Recorder.

25 Jul 1922

Secretary of Chamber now Gehring is appointed USDA crop reporter for district.

10 May 1923

29 Jul 1925

20 Jun 1928

22 Nov 1938

“Miss Edith Roberta Moore, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. L. A. Moore of this city (Tulare) became the wife of Frank A. Gehring, city editor of the Advance, at a quiet but pretty wedding service held this afternoon at the home of the bride’s sister, Mrs. Floyd Byrnes, in Visalia.”

04 Mar 1959

IN PETALUMA IN 1913… RACIST PURE FOOD DRUG LAWS AND A WAR ON EGGS….

“

In 1913, Sonoma County – with a population of 48,500 – had instituted something called “The Roadhouse Ordinance” in a move to “go dry” in a limited way. By 1914, just 64 of the local 110 roadhouses, resorts and hotels remained open. It has been opined that political influence had a bit to do with which ones did not get shuttered.

And, in Petaluma, our Women’s Club proudly celebrated the laying of the cornerstone for their new clubhouse on B Street. It was designed by Petaluma’s Brainerd Jones and several hundred folks showed up for the festivities. Another step into our future that year was the opening of the Petaluma Railroad Depot on Lakeville. Constructed by Northwestern Pacific Railroad at a cost of $7,000, the depot was dedicated that April, with speeches from Mayor Horwege and J.E. Olmsted, of our Chamber of Commerce.

But the big flap in Sonoma County – and mainly in Petaluma – was the looming importation of cheap eggs from China. Our Sonoma County Poultry Producers had appealed via an open letter, to the US Secretary of Agriculture, to take action under the Pure Food Laws, to halt said importation because of what they called, “unsanitary, vile, filthy and unspeakable conditions under which the eggs had been produced in China.” Oh my!

They claimed the hens were getting “no care,” and that it affected the incoming egg’s flavor. Also, those eggs were selling for 10 cents a dozen in San Francisco vs. Petaluma eggs at 21 cents, and the welfare of the US poultry industry was being threatened.

The California Board of Health then undertook an extensive investigation and concluded that the Chinese egg shells, being more porous (they said), had “a tendency to be penetrated by dangerous bacteria.” But this charge was left hanging out there, for possible future quarantine from the Feds, which was not soon coming.

A successful ad campaign, was conducted against egg imports and consumers began demanding that they know how old eggs are, at purchase point. A few months following that publicity, Courier editor Homer Wood stated that, “due to the Poultymen’s Federation, local ranchers have now upped their sales by $75,000 over the months of March and April. They are adding to the prosperity of the county at large. It has been ruinous and impossible Asian competition.”

Petaluma also entered a “P.R.” truck in San Francisco’s parades, with a large banner saying, “The Pure Food Egg Comes From Sonoma County California, Not China.” “Be loyal to your home producer!”

Sound familiar?

Humorously then, a “freak egg” happened to be found in a nest here, half brown and half white, and our Courier wryly opined that this Petaluma hen had been just sitting there, “indignant over the invasion of the brown Chinese egg.”

Meanwhile, “The Egg King of China,” a fellow named E. Block, blew his cool, saying he was angry due to “aspersions cast on the quality of his output, because it was described as the product of scavenger hens.”

Seeing a decrease in his California business, he then said he would prove to the US Department of Agriculture that grounds could not be found for excluding his eggs. That said, he also allowed, “There is more money to be made by shipping to Europe, where eggs are sold by the pound.” He was also, you see, breaking eggs into tin cans, then whipping and hard-freezing them to ship to bakers, and the European market apparently liked that.

But the tough competition continued here on into the Twenties. Author Thea Lowry, in her fine book, “Empty Shells,” said, “In 1921, bargain priced Chinese eggs, selling for six cents a dozen, flooded the market.” The following year, our Chamber of Commerce hired wily promoter Bert Kerrigan to go on the road to lobby for help. And eventually, writes Lowry, “Congress passed the Fordney-McCumber Bill, which levied an import tariff of 8 cents per dozen on foreign shell eggs.”

And Petaluma was able to continue to boast of itself as “The Egg Basket of The World.” (source)